My practice in Ink art

My practice in Ink art – A detour from fruitful foundation predecessors built?

Chan Sai Lok

Hong Kong artists have enjoyed their privileged position in the rising tide of Chinese style art in the international art scene; while works by the post-80s’ and post 90s’ artists in response to unique Chinese traditions and social changes are less on the spotlight, Chinese ink art is said to be gaining popularity, albeit its unclear prospect. Hong Kong has been playing her crucial role in modern Chinese history: as the bridge between China and the rest of the world, and a cultural shelter. Literati from southern part of China not only advocated national arts in the colony, but also endeavored to renovate traditional Chinese art with novel ideas from the west. Freeing from conventional media, Artists could show their concern for Chinese culture through new ones like installations and videos. But for those who have found the beauty in ink art, how do they incorporate Chinese cultural traditions into western artistic discourse?

Up and coming young Hong Kong artists specialized in ink art are often generalized as a new generation mixing east and west with inheritance for both Chinese painting and calligraphy. That said, have we ever realized the critical condition young artists have to endure in the pursuit of ink art? Have we ever cared about what cultural habitat these artists need to prosper?

Artistic ideologies and cultural context are simply inseparable from each other. Traditional calligraphy and ink painting could not avoid the hit when feudalism collapsed in China, a time when cultural glory of the literati and painters existed barely in name. We might as well doubt after exploring multitude of ink art trends across dynasties, possibly through our smartphones: How will Howcontemporary ink painting, with deep cultural root, progress when cultural traditions should neither be abandoned nor rigidly followed? Back in 1960s and 70s, Lui Shou-kwan gave lectures at the current School of Continuing and Professional Studies of CUHK, while his students wrote “Lectures on ink paintings” as a detailed account on his revolutionary concepts on Chinese painting. ‘Yuan Tao Painting Society” and “Yi Painting Society”, influenced by Lui, were then established. At a similar time, Mr Liu Guo Sung, grand master of contemporary Taiwanese ink paintings, was appointed the head of Department of Fine Arts in CUHK. He successfully brought new elements into the “New Ink Painting Movement”. “Hong Kong Modern Ink Painting Society” was later founded.

The contrasting terms “Chinese painting” and “western painting” stress the differences in cultural traditions and material application. According to Liu, “ink art” established itself from Wang Wei in Tang Dynasty. It differs from the internal tendency of Chinese painting in the sense that it includes western artistic concepts: intense sense of contemporaneity plus free creativity. It is evidently a detour from the traditional with visual and spiritual correspondence to Chinese traditions. How does the essence of “New Ink Painting Movement” – a chapter in Hong Kong art history back half a century ago, live through till our times?

Successors take the fruits?

Respect for the past and predecessors are two key qualities in Chinese art. It is they which make it differ so much from the rebellious and unruly nature of the west. However, Wucius Wong pointed out clearly in 1950s that “Chinese ink paintings are becoming rigid and standardized, clearly disconnecting itself with times and environment”. It certainly takes much devotion to turn these characteristics a driving force of its development instead of a hindrance. Wilson Shieh, Koon Wai Bong, Pau Mo Ching, Chui Pui Chee, Lai Kwan Ting Sue, Leung Yee Ting Eve, Barbara Choi Tak Yee, Wong Xian Yi, are probably the leading players.

Lai Kwan Ting Sue “Tourists”(Partial), 175cm(H)x 85cm(W), 一Set of two, Ink on paper, 2013Respect for the past – to display traces of artistic traditions in one’s artwork, is not only a theoretical discussion, but sharpening of skills through continual training. Colour filling with a pen in traditional Chinese realist paintings is a negative example showing how lack of refinement in subject matter and skills would devastate an artwork. As it is agreed that there is no way to advance in skills except meticulous training, one can easily see why young artists hoping to master the skills have to win approval from those predecessors, though the latter are not necessarily advantaged.

The background of instructors also counts in an apprenticeship. Pupils will focus on animals drawing if their master is an expert in that area. This is particularly true in arts institutes in China. To be creative may simply mean filling the gap between ink arts and daily life, but it is also like walking a fine line – exploring an area of unknown width and depth by bringing personal elements in the creative process after paying due respect to the past, and to instructors. It’s just a matter of luck when it comes to the ending – you may hurt yourself deep or succeed in detouring from the conventional. Predecessors may criticize the creative approaches as “fun for kids” or “unskillful”, joining the media which tag them as “rebellious”. Frankly, one may be at a loss for words for responses to these comments. Prize-giving might be a common approach to compliment young, talented artists on their creativity in different areas. However, if a young artist practicing ink art is lucky enough to be awarded, he might be worried more than happy, for he has to be psychologically prepared for cold comments from his predecessors. Master and pupil may make good partners supporting each other in the creative process; there are also real examples of master and pupil turning strangers just because they “part their ways”.

Pau Mo Ching《Taking Shapes.Yoga Series》

Endless Prosperity?

Pau Mo Ching’s strikes a perfect balance between respecting the past and creating the new. She personally practices yoga regularly in recent years, and her calligraphy works see a combination of “bridge” and “tree” postures and emotional reflections, just like those expressing their mind through paintings after a joyful trip. This emotion-driven creativity is also seen in Chui Pui Chee’s calligraphy work “Three stages in life”. The semi-cursive script and grass script are historical calligraphic forms, but what strikes the nerves of Hong Kong people are Eason Chan’s hits: “Bicycle”, “When Grapes Ripe” and “Salon”. National arts need injection of youth elements for revival. While it is indisputable that gaps exist in generations practicing ink arts, the aura and underlying rules are what govern the development of talents.

School of Fine Art, CHUK has been playing its central role in Chinese art education. Basics in calligraphy, Chinese painting, scenic painting, animal painting and portrait are all individual subjects. Features on calligraphic history, painting history and Chinese art history consolidate students’ foundation. Students are still allocated time for Chinese art even after the restructure on courses. Students in the School of Visual Arts of Baptist University of Hong Kong, which has a history of less than 10 years, are only focused on visual art courses in their 3rd and 4th year of studies. If they pick relevant electives, they are bound to grasp techniques for all types of Chinese painting mentioned above in just 26 lessons! It is therefore nicknamed “near-professional interest group”. We could only spare ourselves from a lonely, boring creative process if there are support from counterparts, and “knowledgeable listeners” to share our views and feelings.

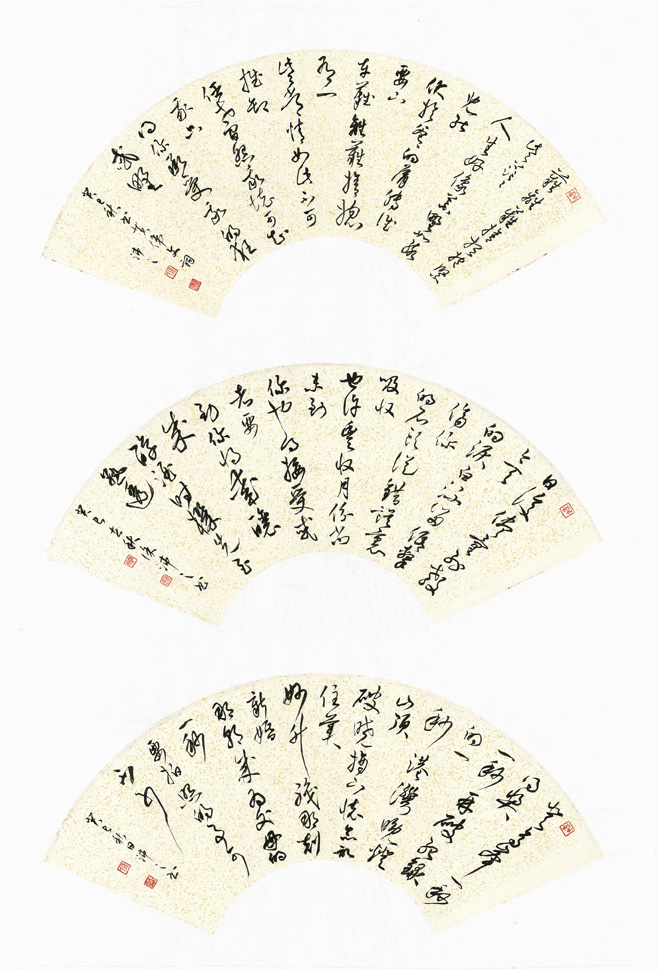

Chui Pui Chi《3 Stages in Life – “Bicycle”, ”When Grapes ripe”, “Salon”》

30cm(H)x 50cm(W),Set of three,Ink on paper fan,2013

Building the Cultural Habitat

Western art has always been the target of the capitalist international art scene or market. Chinese art, on the other hand, is a symbolic cultural identity attractive to foreigners. Ink artworks – a combination of traditional artistic content and foreigners-readable elements, could sell in exhibitions or merchandising platforms, are therefore the most popular. However, that doesn’t bring any positive impact on local cultural discussions. While the market wouldn’t value artworks from the perspective of Chinese art, can exhibitions be viewed this way? We indeed need in-depth discussions like Chiu Kwong-chiu’s search for “vivid charm” – as the supreme aesthetic and appreciation principle, but not as governing rule for creativity. We also need open-minded and daring predecessors in paving new ways. An example would be the late Seeyeu Jat creating human body calligraphy at the invitation from Cosmopolitan back in 1996. It’s high time to restart the poetic yet practical “fulfilling oriental dreams in the west” discussion approach of the New Ink Painting Movement; Exhibitions similar to “The Origin of Dao” held last year by Hong Kong Art Museum, like international academic conferences, need to be run on a continual basis.

History is not meant to be carried to the grave. The city’s once blurred identity has taken shape gradually. As Lui mentioned earlier, “The art and culture Hong Kong builds live on with the city”. With a cultural background distinct from China’s and Taiwan’s, how is Hong Kong’s cultural subjectivity realized? How will the post-millennium “local new ink art” be molded?